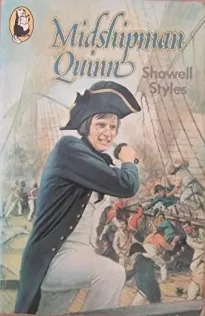

Midshipman Quinn

- Автор: Showell Styles

- Жанр: Исторические приключения / Морские приключения

- Дата выхода: 1956

Читать книгу "Midshipman Quinn" полностью

— 2 —

At three o'clock in the morning, thirty-one hours after Captain Sainsbury had issued his preliminary orders, two boats in line ahead were creeping in towards the French coast. The night was moonless, and the glimmer of stars showed the two black shapes like many-legged beetles. A faint glow of phosphorescence showed each time the oars dipped their blades, but there was no creaking from the muffled rowlocks.

A light breeze had enabled both boats to make the better part of their six-mile voyage under sail. Before the low broken line of the coast had appeared, however, Mr. Gifford had ordered sails in and masts lowered and they had taken to the oars. The cutter was in the lead. Astern of her followed the launch, with Charles Barry at the tiller and Septimus Quinn sitting in the sternsheets beside him. Both had cutlasses at their sides, as had the nine seamen in their boat. Pistols had not been issued, for silence was an essential part of their plan even if they had to beat off an attack.

"Can't be far off the shore now," muttered Barry nervously. "Mr. Gifford will give us the word," replied Septimus reassuringly.

He could feel the slight trembling of Barry's arm. He repressed a wish that he, and not his friend, had been given command of a boat — Charles was so plainly unsure of himself. But Septimus was bound to obey any orders Charles might give, not because he was a year younger but because his name was further down the List at the Admiralty. It was the law of the Navy. When two officers of equal rank were together, the one who had joined first, and whose name was therefore higher on the List, was the senior of the two.

"Cutter's stopped pulling," said Barry suddenly. " 'Vast pulling, launch."

The launch crept alongside the leading boat, and Lieutenant

Gifford's voice came across the intervening space of dark water.

"We're about a mile offshore, Mr. Barry. We'll part here. If my reckoning's correct, we're midway between our landing-points. You know your course?"

"North by west, sir."

"Yes. I'd keep a little north of that. You'll pull five knots, roughly, so if you row for thirty-five minutes and then head in for the shore you'll be in position. Good luck!"

"Aye aye, sir. Good luck to you!"

The cutter's head bore away and she disappeared into the night as the launch turned in the opposite direction and began to move northward.

Most of the previous day had been spent in discussing and preparing the operation, for though it was a small one and likely to be straightforward if all went well, nothing could be left to chance except the actual taking of prisoners. Midshipmen Barry and Quinn knew exactly what they had to do by the time they had finished discussing it with Lieutenant Gifford. They were to land with eight men, leaving the ninth in charge of the boat. Then they were to find the coast road — without being observed — and wait in ambush according to what facilities the roadside offered for concealment. If and when they secured a prisoner, they were to make their way back to the ship independently of Gifford's party. Every effort was to be made to avoid leading the enemy to the beach or otherwise giving away the presence of a British ship.

Tod Beamish (who made one of the launch's crew) carried a small bag slung round his shoulders containing two carefully prepared gags and several short lengths of line for binding the prisoner. Septimus had added an idea of his own by getting the gunner's mate to provide him with a narrow canvas sleeve eighteen inches long and three inches wide. When Mr. Preece asked him what it was for, he replied that prisoners might make a lot of noise even if they were gagged, which made Mr. Preece scratch his grizzled head in bewilderment.

Steadily northward crept the launch, and soon the slightly uneven black line that was the coast began to stand out more sharply against the stars. On their starboard hand the eastern sky was paling when Barry, kneeling in the bottom of the boat and striking flint and steel under cover of his coat, looked at his watch.

"Another three minutes," he announced in a shaky whisper. "Keep pulling, men — and no talking from now on."

The dark shape of the launch moved on for a short distance and then Barry put the tiller over and she headed straight in for the shore. In five minutes they could hear the sound of waves breaking on a beach.

"Not much of a surf," whispered Midshipman Quinn. "We could ground bows-on. It's not likely we'll find anyone about for miles. "

"Unless the French have had warning of us," returned Barry uneasily. "In that case, they may be there — waiting for us."

"Here are the breakers," said Septimus quickly. "Watch your helm, Charles!"

The launch rose on a wavecrest and the white of the surf could be seen ahead. The two bowmen shipped their oars, ready to leap out and drag her bows up the beach when she grounded. Ten strokes, and the keel grated on small shingle. Thirty seconds later the British landing-party was standing on French ground.

"I thought I heard a — a voice," quavered Barry, peering round him in the darkness. He was gripping Midshipman Quinn's arm tightly. "Perhaps it'd be wiser to pull off again and listen."

"Steady, Charles," Septimus whispered urgently in his friend's ear. "The beach is deserted. Better tell Hubbard to keep the launch well offshore until we return, in case anyone comes along."

Barry pulled himself together and gave the order. The launch with her crew of one was shoved off, and the eight men clustered round the two midshipmen ready for further orders. Barry, who was obviously suffering from nervousness, said nothing, and Septimus realised that he would have to take action himself — his senior was for the moment incapable of it.

"If I remember correctly, Mr. Barry," he said in a low voice that the men could hear, "you decided that I should lead the file, as my sight in the dark is better than yours."

"Yes-yes, of course," said Barry hastily. "Pray lead the way, Sep — I mean Mr. Quinn. I will bring up the rear."

"Aye aye," returned Septimus. "Single file, then — every man close up to his leader — no noise. Follow me."

He started up the gentle slope of the shingle. It was impossible to avoid making a noise in crossing it, but soon they came to soft sand with stunted bushes growing here and there and a line of low trees beyond. A small square shape appeared among the trees. Septimus halted the file and went to speak to Barry.

"There's a building in front," he whispered. "I suggest I go on to reconnoitre while you wait here."

"If it's a farm," Charles whispered back, "couldn't we kidnap the farmer and run for it?"

"He wouldn't be the sort of prisoner the captain wants, I fear. I'll go and see where we are."

Without waiting for Barry's agreement, he ran forward. The dawn would soon be here and there was no time to waste.

The line of trees bordered a vineyard, he found, and the square shape was a stone building that seemed deserted. He trotted noiselessly along the edge of the vineyard, thinking what a pity it was that Charles Barry was unable to feel this thrill of excitement at prowling into Bonaparte's territory — territory where discovery would mean death or imprisonment. Septimus had to admit that his friend was showing himself a coward indeed. But he was not convinced that cowardice was part of Barry's character. If only he could make Barry see himself as he really was, force him to prove himself capable of courage in the face of the enemy — and Septimus believed that he was capable of it — he might save his friend from disgrace. But in the midst of a perilous night operation there seemed little chance of scheming for such an occasion.

Here was a gap in the line of trees. A sandy track divided one big vineyard from another, it appeared, and the track was heading directly away from the beach. It was bound to lead to the coast road — if there was one — because the vine harvesters would want to take their produce to market in Perpignan by cart. He need go no further with his reconnaissance. As he turned away, Septimus remembered that the grapes would be nearly ripe. He went to the nearest vine-tree and plucked the biggest bunch he could feel in the darkness, before scuttling back the way he had come.

Part of the Coast of France, with the Place where we landed and took a Prisoner.

From Midshipman Quinn's private Log.

When he felt soft sand under his feet he paused again, to fill the canvas sleeve Mr. Preece had made him. A minute later he was tossing his captured grapes to the seamen, who sucked them thirstily.

"Spoils of war," he said. "All is clear, Mr. Barry. If you will follow, I can bring you to the coast road."

The party of ten, in single fIle, moved silently to the edge of the vineyard and came to the sandy track. Three hundred paces along it brought them within a few yards of its end, where it appeared to join another track. Again Septimus went on alone, moving silently at the very edge of the track. At the junction his suspicions were confirmed. A wide metalled road, obviously a main road of some importance, ran north and south bordered by trees and bushes. He went back and reported this to Barry.

"We can rig an ambush within a short distance of this lane," he added. "I suggest, Mr. Barry, that we take four men each and hide ourselves on the roadside, my party fifty feet from yours. Then, supposing a Frenchman comes along from my direction, I let him pass — you stop him — and I come up from behind to prevent him from escaping."

Barry did not at first reply, probably because he was trying to stop the chattering of his teeth.

"W-would it not be b-better to wait in the lane here?" he suggested at last.

The darkness hid the sharp dig in the ribs which Septimus administered, and he took care that the seamen did not hear his whispered "Pull yourself together!"

"I fancy the road myself," he said aloud. "And we had better get into position quickly if you agree."

Barry seemed to make an effort, and spoke with some decision.

"Very well, then. And we take the first chance we get, and rush our prisoner away down the lane."

Septimus would have liked to say that it would be better to let the first passer-by go free unless he looked like being useful, but he decided that he could not, this time, question Barry's order.

"I'll take Beamish, Rudd, Tipper, and Garraway," he said, since his senior had again fallen into uneasy silence. "Come on, men."

They went forward into the road and Septimus turned to the right along it. He led the way past a stone bridge which crossed a dry stream-bed, and stopped by a thick fringe of bushes. His eyes were well used to the darkness by now, and he could make out the other five halting twenty paces further back and watch them disappear into the roadside thickets. He led his own men into the bushes and told them to make themselves comfortable.

"If you want to scratch yourselves or break twigs," he added, "do it now. And give Beamish plenty of room. I want to listen without any noise from you."

Hoarse chuckles and a chorus of whispered "Aye-ayes" answered him. He settled himself behind a low thorn-bush close to the roadside and prepared to wait.

The stars winked down through the twigs over his head — there was no sign of daybreak there. The "false dawn" that had appeared earlier had not spread over the sky. It would be hard luck, he told himself, if no one came along that road before sunrise, but the attempt would still have to be made. The minutes lengthened out into what seemed like hours, and his straining ears had picked up no sound except the distant murmur of the sea and the occasional high note of an insect. Some sort of stinging fly was bothering the men, and he had to whisper a sharp reprimand when someone let out a hoarse oath. He had scarcely done so when the sound of a man's voice singing reached him.

The seamen heard it too, and crouched in absolute silence. The singing came nearer, and footsteps could now be heard — footsteps as unsteady as the singing. They were approaching from northward, the direction of Perpignan, and would pass the lair of Septimus and his men before reaching Barry's ambush.

Cautiously Septimus poked out his head so that he could look along the road. A dark figure was already in sight, not more than thirty yards away, stumbling along drunkenly. A French farmhand, probably, reeling home after a night's wine-bibbing with his friends in Perpignan. The information that such a man could give wouldn't be much use to a British frigate, thought Midshipman Quinn as the man shambled past only a foot or two from him, raucously singing

"Aupres de ma blonde, Qu'il fait bon, fait bon, fait bon,Aupres de ma blonde, Qu'il fait—"

The singing stopped abruptly, and simultaneously Septimus and his party ran out on to the road. They were in time to see Barry and his four men make an easy capture. The dazed and bewildered labourer — for such he seemed to be — made no resistance and was allowed to make no noise. Brawny arms held him while he was neatly gagged and his hands tied behind him.

"Got him!" Barry said triumphantly as Septimus came up to him. "Now for the shore and back on board!"

"Wait," Septimus begged him urgently. "You speak good French, Charles, don't you? Better than mine?"

"I suppose so," replied Barry with obvious impatience. "But why—"

"Listen, Charles. It's just possible we can do better than this fellow. "

"I'm not going to wait," said Barry nervously. "A cavalry patrol might come along this road any moment."

"Two minutes won't make much difference." Septimus drew his friend away from the group of men. "All I suggest is that you get the party off the road — into the stream-bed by that bridge, if you like — and ask this fellow a few questions."

"But—"

"Pray do as I ask, Charles. Under the bridge we'll be hidden from anyone who passes on the road."

Barry hesitated and then gave in, though he plainly disliked the idea. The seamen pulled their grunting prisoner down the bank of the dried-up stream and into the black shadows of the bridge. The two midshipmen followed.

"Now, Mr. Barry," said Septimus, drawing the cutlass from his belt, "if Beamish takes off that gag, I venture to suggest our prisoner may be able to tell you something of interest. But first, tell him that if he makes any sound above a whisper, I'll cut his throat."

As he spoke he let the point of his weapon rest against the neck of the Frenchman, who squirmed away from it. Barry, whose French was a good deal more fluent than Septimus's, did as he suggested. The gag was taken out, and the prisoner's first choking protests silenced by a gentle pressure of the cutlass-point.

"Ask him if any soldiers pass along this road," muttered Septimus.

Barry repeated it in French. The prisoner, evidently partly sobered by the shock of his capture, replied without hesitation that soldiers did pass, every day. They took supplies from Perpignan to the garrison at Port Vendres. No, he didn't know how many soldiers there were in either town. But he could tell them that there was a big French ship-of-war, the Vengeur, in Port Vendres harbour.

"Is this road patrolled by soldiers?"

Why, of course it was. It was the main coast road, and there were patrols on it day and night, cavalry patrols of twenty men and a sergeant. Prompted by Septimus, Barry asked when the night patrol usually passed that spot. And the answer made both midshipmen jump.

"At this time, messieurs, coming from Perpignan. I am surprised it has not passed already."